|

The

existence of British territory in India, side by

side with territory under British protection and

States wholly under native rule, was a condition of

things neither conducive to peace nor likely to be

of a permanent nature. A single spark dropped among

the warlike races inhabiting that vast peninsula was

often enough to cause wide-spreading conflagration;

and, however agreeable it might be to British

consciences, it would be unphilosophic in the

highest degree to attribute the blame for such

outbreaks exclusively to the native rulers and

people. Trouble broke out early in 1843 which led to

the annexation by the British of Scinde, a fine

territory lying between the Indian Ocean and the

Cutch on the south, and southern Afghanistan and the

Punjab on the north. Scinde had been divided into

three provinces—Hyderabad, Khyrpore, and Meerpore—each

ruled by a group of Ameers or hereditary chiefs,

descended from Beloochee conquerors, who, it was

said, most cruelly oppressed the people under them.

Successive treaties had been effected with these

rulers by the Indian Government, but the disaster

which fell on the British arms in Cabul seems to

have encouraged them to withhold some of the tribute

due by them under the latest treaty, and they began

warlike preparations. In 1842 Lord Ellenborough

appointed Sir Charles Napier Commander-in-Chief of

the British troops in Scinde, with instructions to

inflict signal punishment on any chiefs detected in

treachery, at the same time empowering him to make a

fresh treaty, relieving the Ameers from the payment

of any subsidy for the support of British troops

This treaty was at length signed, though it must be

confessed that the Ameers were only induced to

consent to it by the threatening display of Napier's

force. On February 15, 1843, the British Residency

at Hyderabad was attacked by 8,000 troops with six

guns, led by one or more of the Ameers, and the

garrison of 100 men under Major Outram was driven

out after a gallant resistance.

Napier

marched to Muttaree the following day with a force

of 3,000, attacked the Ameers, who had an army of

22,000 Beloochees, on the morning of the 17th at

Meeanee, six miles from Hyderabad, defeated them,

and captured their whole artillery, ammunition,

baggage, and considerable treasure. The British loss

amounted to 256 killed and wounded. Hyderabad was

occupied, but the Ameer of Meerpore was still under

arms, holding a strong position at Dubba, about four

miles from Hyderabad, with 20,000 men. Napier

attacked him, and a battle lasting for three hours

ended in the complete defeat of Shere Mahomed and

the occupation of Meerpore by the British. Sir

Charles Napier continued warlike operations at

intervals against the hill tribes north of

Shikarpore, and there can be but one opinion of the

masterly way in which he handled the troops under

his command. But the policy of the Governor-General

was open to some difference of opinion. He had

carried things with a high hand in dealing with the

Ameers, and early in 1844 he was recalled by the

unanimous vote of the Court of Directors of the East

India Company, and Sir Henry Hardinge was appointed

in his place.

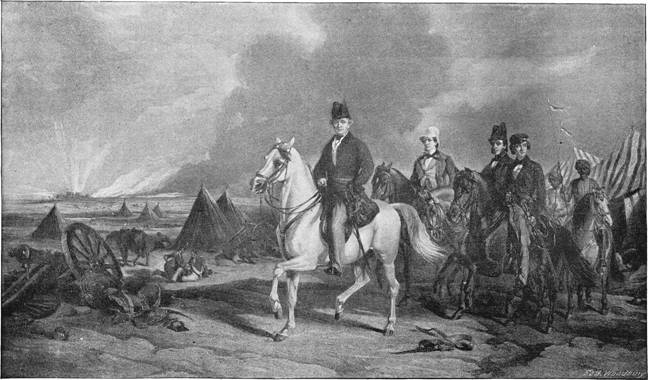

SIR HENRY, AFTERWARDS VISCOUNT, HARDINGE AND HIS

STAFF AT FEROZESHAH

Hardinge

applied himself to the peaceful preparation of

railroad schemes for the development of India, but

at the close of 1845 events again forced the

Government forward on the path of fresh conquest. At

that time the Punjab, a kingdom consisting both of

independent Sikh States and those under British

protection, was under nominal rule of the boy-king,

Dhuleep Singh, and his mother, the Ranee; but his

government at Lahore was distracted by faction and

lay at the mercy of his own powerful army. In

December 1845, the Sikh forces, for some reason

which has never been clearly explained, began

massing on the British frontier, and crossed the

Sutlej, 15,000 or 20,000 strong, on the 13th. Sir

Hugh Gough advanced by forced marches to meet them,

attacked them at Moodkee and defeated them,

capturing seventeen guns. The Sikhs retired to a

strongly-entrenched camp at Ferozeshah, whither

Gough, reinforced by Sir John Littler's division

from Ferozepore, followed them on the 21st. The Sikh

army was now upwards of. 50,000 strong, with 108

heavy guns in fixed batteries. The British force

consisted of 16,70o men and sixty-nine guns, chiefly

horse artillery. There ensued one of the severest

conflicts in the history of our Indian Empire.

Beginning on the 21st it lasted through part of the

22nd, and ended in the gallant Sikhs being driven

across the Sutlej with the loss of many killed and

wounded, and no less than seventy guns. The

Governor-General, Sir Henry Hardinge, acted as a

volunteer, second in command to Sir Hugh Gough, in

this memorable action.

Early in

January 1846, Sirdar Runjoor Singh, again advancing

towards the 'frontier, took up a strong position on

the British side of the Sutlej, threatening Gough's

line of communications with Loodiana. Major-General

Sir Harry Smith attacked him at Aliwal on January

28, and, notwithstanding the great superiority in

numbers of the enemy, obtained a brilliant victory

over the Sikhs, capturing their camp and fifty-two

guns. But more fighting had to be done before the

army of the Punjab could be finally subdued. The

Sikhs still lay at Sobraon with 30,000 of their best

troops, defended by a triple line of breast works,

flanked by redoubts, and armed with seventy guns.

Here Sir Hugh Gough attacked them on the morning of

February 10, the Governor-General again being

present as second in command. At nine o'clock, after

an hour's cannonade, Brigadier Stacey advanced to

storm the entrenchments with four battalions, which

behaved with splendid gallantry under a very heavy

and well-directed fire. They stormed the position,

and, being well supported, forced their way into the

fortress. By eleven o'clock all was over. The Sikhs

were in full flight across the Sutlej, leaving

behind them piles of dead and wounded, sixty - seven

guns, 200 camel swivels, and all their baggage and

ammunition. The British loss consisted of 320

killed, including seventeen officers (among whom

were Major-General Sir Robert Dick, General McLaren,

and Brigadier Taylor), and 2,063 wounded, including

139 officers. But the carnage among the Sikhs was

far more terrible. It is supposed that not less than

eight or ten thousand of them perished in action or

were drowned in crossing the river under the fire of

the British artillery. On February 22 Gough occupied

the citadel of Lahore ; the Governor-General issued

a proclamation from that place, and a treaty was

subsequently concluded establishing Dhuleep Singh as

Maharajah, tributary to the British Government.

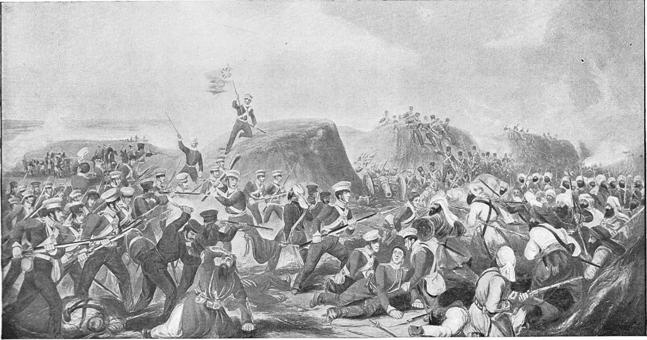

THE BATTLE OF SOBRAON, February

so, 0846.

This

illustration is reproduced from a popular, but

somewhat quaint, coloured print representing the 3rd

Regiment, with Major-General Sir Henry Smith's

division, in action at Sobraon. It forms an

instructive contrast with the military prints of the

present day.

Site Copyright Worldwide 2010. Text and

poetry written by

Sir Hubert Maxwell is not to be reproduced without

express Permission.

|